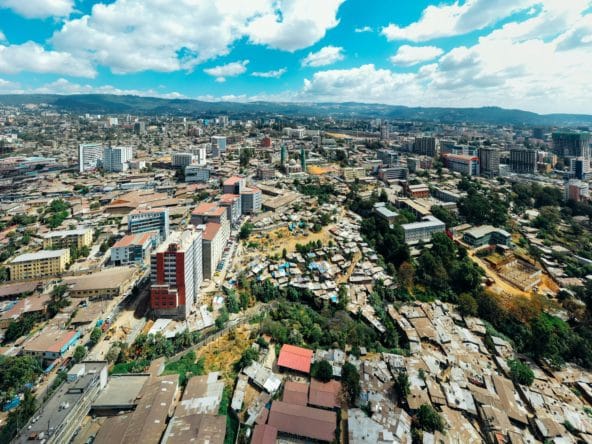

A Tale of Two Homes: Understanding Kenya’s “Owning in the Village, Renting in the City” Phenomenon (2025)

A distinctive and deeply ingrained homeownership pattern shapes Kenya’s real estate landscape: the phenomenon of “owning in the village, renting in the city.” Statistics suggest that around 61% of Kenyans own homes; however, for a significant portion of this demographic, particularly those working in urban centers, this ownership is rooted in rural areas, often ancestral land, while their daily lives unfold in rented urban accommodations. This dual living reality is a fascinating interplay of economic pressures, financing accessibility, and profound cultural ties.

Economic Realities: The Urban Affordability Gap

The primary driver of this trend is the stark contrast in property costs between urban and rural Kenya.

- High Urban Property Prices: The cost of land and housing in major cities like Nairobi has escalated significantly over the years, placing urban homeownership beyond the reach of many average-income earners.

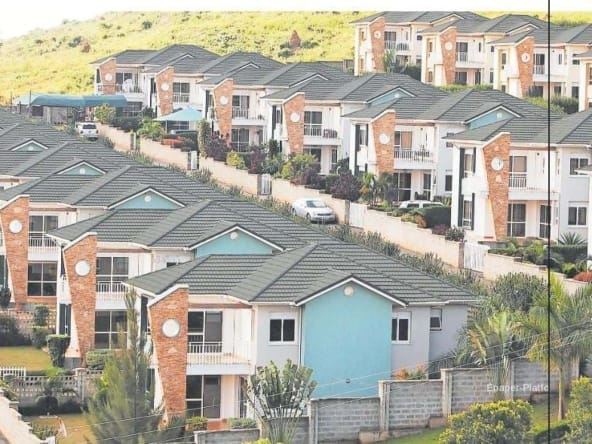

- Rural Affordability: In contrast, land in rural areas is often considerably more affordable, and in many cases, individuals may have access to inherited family land, reducing the initial acquisition cost to zero. This economic disparity makes building or owning a home in the village a more realistic and attainable goal for a large segment of the population, even if their employment necessitates living in a city.

Financing and Land Ownership Trends

Access to financing further reinforces this pattern:

- Limited Mortgage Access: As highlighted previously, formal mortgage uptake in Kenya is very low (less than 1% of adults), with high interest rates and stringent lending criteria posing significant barriers for urban property acquisition.

- Alternative Rural Financing: Acquiring rural land or undertaking construction in the village is often financed through more accessible means:

- Cash Savings: Accumulated personal savings.

- Chamas (Informal Savings Groups): Pooled resources from community or family-based savings groups.

- SACCO Loans: Loans from Savings and Credit Co-operative Societies, which are often more flexible than bank mortgages.

- Family Contributions: Financial support from extended family members. These alternative financing routes make rural property development more feasible for many compared to the hurdles of securing urban mortgages.

Deep-Seated Cultural Roots

Cultural factors play a pivotal role in the “owning in the village” aspect:

- Ancestral Land and Heritage: Rural land is frequently ancestral land, passed down through generations. This land carries deep sentimental value and represents a connection to one’s roots, family history, and community.

- Retirement Destination: Many Kenyans view their rural home as their eventual retirement destination, a place of peace and belonging after their working years in the city.

- Holiday Homes and Family Gatherings: The rural home often serves as a holiday retreat and a central point for family gatherings and cultural ceremonies.

- Sense of Belonging: Building a home on ancestral land provides a strong sense of identity and community that the more individualistic and transient nature of city life may not always offer.

Implications of Dual Living

This dual living strategy has several implications:

- Sustained Urban Rental Demand: It ensures a continuous demand for rental properties in urban centers.

- Rural Development: It drives construction and economic activity in rural areas.

- Social and Economic Ties: It maintains strong social and economic linkages between urban and rural populations.

- Investment Patterns: It influences how individuals allocate their long-term investment capital, prioritizing rural homeownership.

Conclusion:

The “owning in the village, renting in the city” phenomenon is a pragmatic and culturally resonant adaptation to Kenya’s socio-economic realities. It reflects a blend of financial prudence, limited access to urban housing finance, and an enduring connection to ancestral heritage. As urban property prices continue to pose challenges, this unique dual living strategy is likely to remain a defining characteristic of Kenyan homeownership patterns for the foreseeable future.